Alice Creischer

Der Hut spricht, der Rechen spricht

es flüstert die Sense

zum Ohr im Gras:

8760 Stunden hat das Jahr.

1200 Stunden verbraucht ein Arbeitsplatz.

40 Jahre arbeiten

bei 80 Jahren Lebenserwartung

sind 48.000 Stunden.

Das Leben hat aber

700.800 Stunden

in Deutschland

in Deutschland

ist der Anteil der Arbeitszeit

am Leben

nur 7 Prozent.

Zum Ohr im Gras spricht der Hut

der Rechen spricht

es flüstert die Sense zum Lid:

Given the speed of light in fiber

it is possible

to send

an order from New York to Chicago

and back in 12 milliseconds.

It gives the occasion to be

the first to exploit

the discrepancies between

prices in Chicago and prices in New York.

A millisecond is a thousandth of a second

A tenth of the time it takes you

to blink your eyes,

if you blink

as fast as you can.

Zum Lid zischt die Sense

pass auf, du,

denk bloß nicht, du

dass du das verstecken kannst

unterm Deckel aus Haut,

im Traum im Schlaf

und die Augen die laufen darin

umher wie die Vögel tun

vor dem Wirt

der anschreibt

genau und genau

deinen Anteil von Arbeit

im Leben

an die Tür

mit unauslöschbarer Kreide

und denk bloß nicht,

dass du das auswedeln kannst

mit deinem Wimperngeklimper

und lass die Augen stehn

still in der Mitte

reglos

gefroren

vom Schreck mir zu lauschen im Gras

Und denk bloß nicht

Und untersteh dich

du!

zu denken ich sei eine Grille

Sources / text

Peter Hartz: Die Job Revolution, Frankfurt 2003

Michael Lewis, Flash Boys, A Wall Street Revolt, New York, 2014

Sources / picture

Camille Pissarro, Le repos, paysanne couchée dans l´herbe, 1882

Maximilien Luce, A Street in Paris in May 1871, 1903 – 1905

Fotos: London Riots, 2011

The hat speaks, the rake speaks

the scythe murmurs

to the ear in the grass:

8760 hours has the year.

1200 hours consumes a job.

40 years of work

with 80 years life expectancy

are 48,000 hours.

But life has

700.800 hours

in Germany.

In Germany

the share of working time

of life is

only 7 percent.

To the ear in the grass speaks the hat

the rake speaks

it whispers the scythe to the eyelid:

Given the speed of light in fiber

it is possible

to send

an order from New York to Chicago

and back in 12 milliseconds.

It gives the occasion to be

the first to exploit

the discrepancies between

prices in Chicago and prices in New York.

A millisecond is a thousandth of a second

A tenth of the time it takes you

to blink your eyes,

if you blink

as fast as you can.

To the lid the scythe sizzles

Watch out, you,

Don't you think, you

that you can hide it

under the lid of skin

the dream in sleep

and the eyes that run in it

around like birds do

before the host

who writes

exactly and precisely

your share of work

in life

on the door

with inerasable chalk

and do not think

that you can wipe it out

with your batting eyelashes

and let your eyes stand still

still in the middle

motionless

frozen

from the fright to listen to me in the grass

And do not think

And don’t you dare

you!

To think that I am a cricket

Sources / text

Peter Hartz: Die Job Revolution, Frankfurt 2003

Michael Lewis, Flash Boys, A Wall Street Revolt, New York, 2014

Sources / picture

Camille Pissarro, Le repos, paysanne couchée dans l´herbe, 1882

Maximilien Luce, A Street in Paris in May 1871, 1903 – 1905

Fotos: London Riots, 2011

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

Harmonizing the Elements Within- Healing Sounds

A Neigong 內功 practice presented by Lingji Hon 韓靈芝

I’d like to offer a Taoist perspective of humanity’s relation to the Universe, through sharing the

beloved Chinese creation myth with you. According to the legend, before our universe began,

there was merely a giant cosmic egg.

Inside the egg, forces swirled unanimously- everything and nothing all at once.

This state is known as Wuji 無極, Supreme Nothing- or Primordial Singularity.

Inside the egg, slept a giant named Pan Gu 盤古. One day, Pan Gu awoke, and being alone in

this cosmic egg- he became quite bored. So he swung his axe, and cut the egg in half.

The light part rose and became heaven.

The heavy part sank and became earth.

This state is known as Taiji 太極, Supreme Ultimate. Primordial Polarity.

Pan Gu was worried that heaven and earth would reunite, so he stood up to hold them apart.

Eventually, the immense effort of separating heaven and earth exhausted him, and he died.

His left eye became the sun.

His right eye, the moon.

His flesh became the mountains and valleys.

His blood, the oceans and rivers

And his hair became the trees and flowers.

Pan Gu not only separated heaven and earth, but his body became the new world.

One day, the goddess Nu Wa 女媧, a goddess with the body of a woman, and the tail of a

snake, found herself alone in this new world created by Pan Gu.

Sitting on a riverbank and gazing at her reflection, she decided to create creatures in her own

image.

Slowly, she began to mold figures out of mud from the riverbed, she blew into their mouths, and

they sprang to life- the first humans!

Later- Nu Wa saves humanity by patching a great hole in the sky with her body- becoming the

sky herself.

Within this legend we feel our psyche’s deep memory of being beyond human, and our earliest

efforts to understand our relation to the vastness of the universe- body becomes the world, and

the world becomes body.

All elements and identities of and from our world transform interchangeably.

This reflects an essential concept that is integral to Chinese culture and Taoist- the indigenous

religion of China’s- philosophy.

Macrocosm reflects Microcosm.

Outer mirrors inner.

To understand, nurture and protect the world and the universe we live in, we must first go

inward, and understand, nurture and protect ourselves.

There are 2 main schools of Taoist Alchemy.

Waidan 外丹- External Elixir, creating potions and medicines out of plants, minerals, and other

substances from our surroundings.

And Neidan 內丹- Internal Elixir- creating the remedy within our own body- drawing on our

body’s connection and resonance to nature to regenerate and heal ourselves.

Through going inward and balancing the elements within- inner harmony and compassion may

radiate outward to nurture, heal and protect our communities and environments.

Today, it is my great pleasure to share a beloved Neidan practice with you, from my Lineage-

Long Men Pai 龍門派, the Dragon Gate Alchemical School.

A practice that uses healing sounds to harmonize and balance the elements within.

The essence of each of the 5 elements resides in a vital organ.

Each organ is associated with a color, a season, a direction, an emotional intelligence, and has

a specific responsibility in maintaining balance and harmony within the organism, just as the

elements of nature must also interact and exchange with each other. There must be free flow of

energy between each balanced organ for the maintain the organism’s health and wellbeing.

Through internal practice we seek not only to nurture and vitalize our organs’ healthy and

harmonious flow and exchange between one another we also seek to establish emotional

balance through developing awareness and sensitivity in listening to each organ’s unique

intelligence.

The element of WOOD in Chinese 5 element theory is bamboo, which is hollow, so it is also the

element of WIND. It resides in the LIVER, and is responsible for connectivity of the organism, it

is associated with the season Spring, the color green, the direction east, with the emotion of

anger- which finds completion as compassion and the desire for justice.

Which is incomplete compassion.desire for justice, a sense of self-worth, and righteousness.

The element of FIRE resides in the HEART- it is responsible for warming the body, and is

considered the seat of consciousness, associated with summer, the color red, the direction

south, and with the emotion of love or joy- which can become jealousy, or addiction to excessive

thrills when out of balance.

The element of EARTH- resides in the SPLEEN- responsible for storage- associated with late

summer, the color ochre *yellow* , the direction of center, and with the emotion of worry, stress,

overthinking- when in balance, it is restored to the will to nurture.

The element of METAL resides in the LUNGS- responsible for cooling the organism, associated

with autumn, the color white, the direction west, the emotion of grief- which blossoms into

acceptance.

The element of WATER resides in the KIDNEYS- responsible for distribution- associated with

winter, the color dark blue-black, the direction north, the emotion of fear when out of balance,

and in balance is peace, meditation, courage, instinct.

This practice uses healing sounds, mudra, and gentle movements to communicate with each

organ, establishing balance and harmony between the vital organs and emotional equilibrium.

Now we will begin the practice!

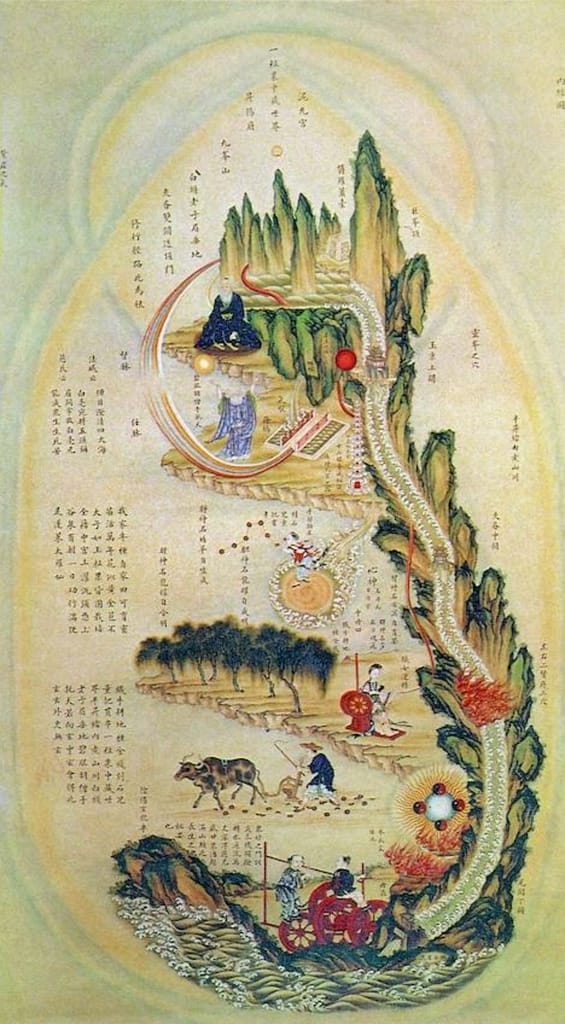

Neijing tu 內經圖- Taoist Diagram of the Inner

Landscape or “Diagram of Interior Lights”

Wojciech Kosma

rzeko rzeko

dlaczego

wciąż robię ci coś niewyobrażalnego

może żebym mógł sobie wyobrazić siebie innego

rzeko rzeko

dlaczego

muszę ci robić wciąż coś niewybaczalnego

może żebym wybaczyć mógł sobie coś

rzeko rzeko

dlaczego sprawiam ci ból dlaczego

może kiedy widzę ciebie cierpiącą

zobaczę siebie cierpiącego

dlatego

przecież ja też jestem rzeką

przecież ja też jestem rzeką

płynę bólem jak ty bardzo

rzeko rzeko

dlaczego tak wstydzę się być rzeką

mamy tyle wspólnego

rzeko rzeko

płynę żalem

nie muszę się wstydzić wcale

płynę cierpieniem

wsiąkam w ziemię

jak ty wsiąkam

rozlewam się po łąkach

na pnie

na liście

na kamienie

uczę się od ciebie

rzeko rzeko

chcę być jak ty taką

chcę być jak ty taką

rzeko rzeko

popłynę z tobą

zróbmy razem błoto

rozlejmy się każdą łąką

każdym bólem

nie różnimy się w ogóle

czuję to przez skórę

czuję cię w sobie

płyniemy obie

płyniemy sobie

cierpieniem ale też euforią

dzikością

zajebistością

żyznością

dlaczego udaję wciąż

wciąż

i wciąż

że nie jestem rzeką

dlaczego

dlaczego

traktuję cię tak nieludzko

przecież płyniemy tą samą wodą

przecież płyniemy tą samą wodą

dlaczego krzywdzę cię tak okrutnie

przecież wsiąkamy w tą samą ziemię

tak samo przyjaźnimy się z ogniem

z wiatrem

z chmurami

całymi swoimi ciałami

całymi swoimi smutkami

całymi swoimi radościami

całymi strumieniami

deszczem

czy możesz mi wybaczyć jeszcze

czy możesz mi wybaczyć jeszcze

przyrzekam że płynie we mnie rzeka

przyrzekam że płynie we mnie rzeka

przyrzekam że płynie we mnie rzeka

przyrzakam że nie będę udawał że nie płynie we mnie rzeka

river oh river

why

do i keep doing the unimaginable to you

maybe so that I can imagine myself differently

river oh river

why

do i have to keep doing something unforgivable to you

maybe so that i can forgive myself

river oh river

why do i cause you pain why

maybe when i see you suffering

i will see myself suffering

that’s why

because i too am a river

i am a river too

i flow with pain like you very much

river oh river

why am i so ashamed to be a river

we have so much in common

river oh river

i’m flowing with grief

i’m not ashamed

i flow with suffering

i soak in the earth

like you i soak

i spill over the meadows

on the trunks

on the leaves

on the stones

i learn from you

river oh river

i want to be like you

i want to be like you

river oh river

i’ll flow with you

let’s make mud together

let’s spill on every meadow

every pain

we are not different

i can feel it through my skin

i can feel you inside me

we both flow

we flow with each other

with suffering but also with euphoria

ferocity

awesomeness

fertility

why do i keep pretending

on and on

that I’m not a river

why

why

do i treat you so inhumanly

we’re flowing with the same water

we’re flowing with the same water

why do i hurt you so cruelly

after all we soak in the same soil

we are friends in the same way with fire

with wind

with clouds

with the the entirety of our bodies

with the entirety of our sorrows

with the entirety of our joys

with entire streams

rain

can you still forgive me

can you still forgive me

i swear there’s a river inside me

i swear there’s a river inside me

i swear there’s a river inside me

i swear i won’t pretend that there isn’t a river inside me

Abridged version of Underground Man by Gabriel Tarde, translated by Cloudesley Brereton.

First published in 1896 as Fragment d’histoire future. Edited by Thomas Love

It was towards the end of the twentieth century of the prehistoric era, formerly called the

Christian, that took place, as is well known, the unexpected catastrophe with which the present

epoch began, that fortunate disaster which compelled the overflowing flood of civilisation to

disappear for the benefit of mankind.

The zenith of human prosperity seemed to have been reached in the superficial and

frivolous sense of the word. For the last fifty years, the final establishment of the great Asiatic-

American-European confederacy, and its indisputable supremacy over what was still left, here

and there, in Oceania and central Africa of barbarous tribes incapable of assimilation, had

habituated all the nations, now converted into provinces, to the delights of universal and

henceforth inviolable peace. It had required not less than 150 years of warfare to arrive at this

wonderful result. Yet of all this warlike mania there only remained a vague poetic remembrance.

Forgetfulness is the beginning of happiness, as fear is the beginning of wisdom.

The Universe breathed again. It yawned a little no doubt, but it revelled for the first time

in the fulness of peace, in the almost gratuitous abundance of every kind of wealth. It burst into

the most brilliant efflorescence, or rather display of poetry and art, but especially of luxury, that

the world had as yet seen. It was just at that moment an extraordinary alarm of a novel kind,

justly provoked by the astronomical observations made on the tower of Babel, which had been

rebuilt as an Eiffel Tower on an enlarged scale, began to spread among the terrified populations.

On several occasions already the sun had given evident signs of weakness. From year to

year his spots increased in size and number, and his heat sensibly diminished. People were lost in

conjecture. Was his fuel giving out? Had he just traversed in his journey through space an

exceptionally cold region? No one knew. Whatever the reason was, the public concerned itself

little about the matter, as in all that is gradual and not sudden. The “solar anæmia”… had merely

become the subject of several rather smart articles in the reviews. In general, the savants, in their

well-warmed studies, affected to disbelieve in the fall of temperature, and, in spite of the formal

indications of the thermometer, they did not cease to repeat that the dogma of slow evolution,

and of the conservation of energy combined with the classical nebular hypothesis, forbade the

admission of a sufficiently rapid cooling of the solar mass to make itself felt during the short

duration of a century, much more so during that of five years or a year.

However, the winter of 2489 was so disastrous, it was actually necessary to take the

threatening predictions of the alarmists seriously. One reached the point of fearing at any

moment a “solar apoplexy.” That was the title of a sensational pamphlet which went through

twenty thousand editions. The return of the spring was anxiously awaited.

The spring returned at last, and the starry monarch reappeared, but his golden crown was

gone, and he himself well-nigh unrecognisable. He was entirely red. The meadows were no

longer green, the sky was no longer blue… all had suddenly changed colour as in a

transformation scene. Then, by degrees, from the red that he was he became orange. And so

during several years he was seen to pass, and all nature with him, through a thousand

magnificent or terrible tints—from orange to yellow, from yellow to green, and from green at

length to indigo and pale blue. So many colours, so many new decorations of the chameleon-like

universe which dazzled the terrified eye, which revived and restored to its primitive sharpness

the rejuvenated sensation of the beauties of nature, and strongly stirred the depths of men’s souls

by renewing the former aspect of things.

At the same time disaster succeeded disaster. The entire population of Norway, Northern

Russia, and Siberia perished, frozen to death in a single night; the temperate zone was decimated,

and what was left of its inhabitants fled before the enormous drifts of snow and ice, and

emigrated by hundreds of millions towards the tropics. The telegraph successively informed the

capital, now of immense trains caught in the tunnels under the Pyrenees, the Alps, the Caucasus,

or Himalayas, in which they were imprisoned by enormous avalanches, which blocked

simultaneously the two issues; now that some of the largest rivers of the world—the Rhine, for

instance, and the Danube—had ceased to flow, completely frozen to the bottom, from which

resulted a drought, followed by an indescribable famine, which obliged thousands of mothers to

devour their own children. What calamities! What horrors! My pen confesses its impotence to

retrace them. Besides how can we tell the story of disasters which were so complete they often

simultaneously overwhelmed under snow-drifts a hundred yards deep all that witnessed them, to

the very last man.

All that we know for certain is what took place at the time towards the end of the twenty-

fifth century in a little district of Arabia Petræa. Thither had flocked for refuge, in one horde

after another, wave after wave, with host upon host frozen one on the top of another, as they

advanced, the few millions of human creatures who survived of the hundreds of millions that had

disappeared. They transported hither by reason of the relative warmth of its climate, I will not

say the seat of Government—for, alas! Terror alone reigned—but an immense stove which took

its place. Of the beautiful human race, so strong and noble, formed by so many centuries of effort

and genius by such an intelligent and extended selection, there would soon have been only left a

few thousands, a few hundreds of haggard and trembling specimens, unique trustees of the last

ruins of what had once been civilisation.

In this extremity a man arose who did not despair of humanity. His name has been

preserved for us. By a singular coincidence he was called Miltiades, like another saviour of

Hellenism. In the middle of the central state shelter, a huge vaulted hall with walls ten yards

thick, without windows, surrounded with a hundred gigantic furnaces, and perpetually lit up by

their hundred flaming maws, Miltiades one day appeared.

The remnant of the flower of humanity, of both sexes, splendid even in its misery, was

huddled together there. They did not consist of the great men of science with their bald pates, nor

even the great actresses, nor the great writers, whose inspiration had deserted them, nor the

consequential ones now past their prime, but the enthusiastic heirs of their traditions, their

secrets, and also of their vacant chairs, that is to say, their pupils, full of talent and promise. Not

a single university professor was there, but a crowd of deputies and assistants; not a single

minister, but a crowd of young secretaries of state. Not a single mother of a family, but a bevy of

artists’ models, admirably formed, and inured against the cold by the practice of posing for the

nude; above all, a number of fashionable beauties, who had been likewise saved by the excellent

hygienic effect of daily wearing low dresses, without taking into account the warmth of their

temperament. Among them it was impossible not to notice the Princess Lydia, owing to her tall

and exquisite figure, the brilliancy of her dress and her wit, of her dark eyes and fair complexion,

owing in fact to the radiance of her whole person. She had carried off the prize at the last grand

international beauty competition, and was accounted the reigning beauty of the drawing-rooms

of Babylon. What a different set of individuals from that which the spectator formerly surveyed

through his opera-glass from the top of the galleries of the so-called Chamber of Deputies!

Youth, beauty, genius, love, infinite treasures of science and art, writers whose pens were of pure

gold, artists with marvellous technique, singers one raved about, all that was left of refinement

and culture on the earth, was concentrated in this last knot of human beings, which blossomed

under the snow like a tuft of rhododendrons, or of Alpine roses at the foot of some mountain

summit. But what dejection had fallen on these fair flowers! How sadly drooped these manifold

graces!

At the sudden apparition of Miltiades every brow was lifted, every eye was fastened upon

him. He was tall, lean, and wizened, in spite of the false plumpness of his thick white furs. He

requested leave to speak. It was granted him. He mounted a platform, and such a profound

silence ensued, one might have heard the snow falling outside, in spite of the thickness of the

walls.

“The situation is serious,” said he, “nothing like it has been seen since the geological

epochs. The hour has come to ascertain to what extent it is true to say and to keep on repeating,

that all our energy, all our strength, whether physical or moral, comes to us from the sun. The

calculation has been made: in two years, three months, and six days, if there still remains a

morsel of coal there will not remain a morsel of bread! Therefore, if the source of all force, of all

motion, and all life is in the sun, and in the sun alone, there is no ground for self-delusion: in two

years, three months, and six days, the genius of man will be quenched, and through the gloomy

heavens the corpse of mankind, like a Siberian mammoth, will roll for everlasting, incapable

forever of resurrection.

“But is that the case? No, it is not, it cannot be the case. With all the energy of my heart,

which does not come from the sun—that energy which comes from the earth, from our mother

earth buried there below, far, far away, forever hidden from our eyes—I protest against this vain

theory, and against so many articles of faith and religion which I have been obliged hitherto to

endure in silence. The earth is the contemporary of the sun, and not its daughter; the earth was

formerly a luminous star like the sun, only sooner extinct. It is only on the surface that the earth

is devoid of movement, frozen and paralysed. Its bosom is ever warm and burning. It has only

concentrated its fire within itself in order to preserve it better. There lies a virgin force that is

unexploited, a force superior to all that the sun has been able to generate for our industry by

waterfalls which to-day are frozen, by cyclones which now have ceased, by tides which to-day

are suspended; a force in which our engineers, with a little initiative, will find a hundredfold the

equivalent of the motive power they have lost. It is no more by this gesture (the speaker raises

his finger to heaven), that the hope of salvation should henceforth be expressed, it is by this one.

(He lowers his right hand towards the earth….) We must say no more: ‘Up there!’ but, ‘below!’

Let us descend into these depths; let us make these abysses our sure retreat. The earth calls us to

its inner self. For many centuries it has lived separated, so to say, from its children, the living

creatures it produced outside during its period of fecundity before the cooling of its crust! After

its crust cooled, the rays of a distant star alone, it is true, have maintained on this dead epidermis

their artificial and superficial life which has been a stranger to her own. But this schism has

lasted too long. It is imperative that it should cease. It is time to follow Empedocles, Ulysses,

Æneas, Dante, to the gloomy abodes of the underworld, to plunge mankind again in the fountain

from which it sprang, to effect the complete restoration of the exiled soul to the land of its birth!”

The speaker next entered into lengthy details on the Neo-troglodytism which he

pretended to inaugurate as the acme of civilization. He had no trouble in proving that, on

condition of burrowing sufficiently deep into the ground below, they would find a deliciously

gentle warmth, an Elysian temperature. It would be enough to excavate, enlarge, heighten, and

extend the galleries of already existing mines in order to render them habitable and comfortable

into the bargain. The electric light, supplied entirely without expense by the scattered centres of

the fire within, would provide for the magnificent illumination both by day and night of these

colossal crypts, these marvellous cloisters, indefinitely extended and embellished by successive

generations. With a good system of ventilation, all danger of suffocation or of foulness of air

would be avoided. In short, after a more or less long period of settling in, civilised life could

unfold anew in all its intellectual, artistic, and fashionable splendour, as freely as it did in the

capricious and intermittent light of natural day, and even perhaps more surely.

Miltiades continued: “However extraordinary the catastrophe which has befallen us and

the means of escape which is left us may seem in appearance, a little reflection will suffice to

prove to us that the predicament in which we are, must have been repeated a thousand times

already in the immensity of the universe, and must have been cleared up in the same fashion,

being inevitably and normally the final phase in the life-drama of every star. The astronomers

know that every sun is bound to become extinct; they know, therefore, that in addition to the

luminous and visible stars, there are in the heavens an infinitely greater number of extinct and

rayless stars which continue endlessly to revolve with their train of planets, doomed to an

eternity of night and cold. Well, if this is the case, I ask you: Can we suppose that life, thought,

and love, are the exclusive privilege of an infinite minority of solar systems still possessed of

light and heat, and deny to the immense majority of gloomy stars every manifestation of life and

animation, the very highest reason for their existence? Thus lifelessness, death, the void in

movement would be the rule; and life the exception! Thus the nine-tenths, the ninety-nine

hundredths, perhaps, of the solar systems, would idly revolve like senseless and gigantic mill-

wheels, a useless encumbrance of space. That is impossible and idiotic, that is blasphemous. Let

us have more faith in the unknown! Truth, here as everywhere else, is without doubt the

antipodes of appearance. All that glitters is not gold. These splendid constellations which attempt

to dazzle us are themselves relatively barren. Their light, what is it? A transient glory, a ruinous

luxury, an ostentatious squandering of energy, born of illimitable senselessness. But when the

stars have sown their wild oats, then the serious task of their life begins, they develop their inner

resources. For frozen and sunless without, they literally preserve in their inviolate centres their

unquenchable fire, defended by the very layers of ice. There, finally, is to be relit the lamp of

life, banished from the surface above. For a last time, therefore, let us look upwards in order

there to find hope. Up there innumerable races of mankind underground, buried, to their supreme

joy, in the catacombs of invisible stars, encourage us by their example. Let us act like them, let

us like them withdraw to the interior of our planet. Like them, let us bury ourselves in order to

rise again, and like them let us carry with us into our tomb, all that is worthy to survive of our

previous existence.

“In our new ark, mysterious, impenetrable, indestructible, we shall carry with us neither

plants nor animals. These types of existence are annihilated; these rough drafts in creation, these

fumbling experiments of Earth in quest of the human form are forever blotted out. Let us not

regret it. In place of so many pairs of animals which take up so much room, of so many useless

seeds, we will carry with us into our retreat the harmonious garland of all the truths in perfect

accord with one another; of all artistic and poetic beauties, which are all members one of another,

united like sisters, which human genius has brought to light in the course of ages and multiplied

thereafter in millions of copies: all of which will be destroyed save a single one, which it will be

our task to guarantee against all danger of destruction. We shall establish a vast library

containing all the principal works, enriched with cinematographic albums. We shall set up a vast

museum composed of single specimens of all the schools, of all the styles of the masters in

architecture, sculpture, painting, and even music. These are our real treasures, our real seed for

future harvests, our gods for whom we will do battle till our latest breath.”

The speaker stepped down from the platform in the midst of indescribable enthusiasm:

the ladies crowded round him. They deputed Lydia to bestow on him a kiss in the name of them

all. Blushing with modesty the latter obeyed, and the applause redoubled. The thermometers of

the shelter rose several degrees in a few minutes.

Never was so magnificent a plan so promptly carried out. From that very day all these

exquisite and delicate hands set to work, aided, it is true, by incomparable machines. Before a

year was out the galleries of the mines had become sufficiently large and comfortable,

sufficiently decorated even and brilliantly lighted, to receive the vast and priceless collections of

all kinds, which it was their object to place in safety there, in view of the future. The day at

length arrived on which, all the intellectual inheritance of the past, all the real capital of

humanity having been rescued from the general shipwreck, the castaways were able to go down

in their turn, having henceforth only to think of their own preservation. How great in fact was

their amazement and their ecstasy! They expected a tomb; they opened their eyes in the most

brilliant and interminable galleries of art they could possibly see, in salons more beautiful than

those of Versailles, in enchanted palaces, in which all extremes of climate, rain, and wind, cold

and torrid heat were unknown; where innumerable lamps, veritable suns in brilliancy and moons

in softness, shed unceasingly through the blue depths their daylight that knew no night.

In truth, if our change of condition has demanded some sacrifices, it is not an illusion to

declare that the balance of advantage is immensely greater. What in comparison with this

unparalleled revolution is the most renowned of the petty revolutions of the past which to-day

are treated so lightly, and rightly so, by our historians. One wonders how the first inhabitants of

these underground dwellings could, even for a moment, regret the sun, a mode of lighting that

bristled with so many inconveniences. The sun was a capricious luminary which went out and

was relit at variable hours, shone when it felt disposed, sometimes was eclipsed, or hid itself

behind the clouds when one had most need of it, or pitilessly blinded one at the very moment one

yearned for shade! Every night,—do we really realise the full force of the

inconvenience?—every night the sun commanded social life to desist and social life desisted.

Humanity was actually to that extent the slave of nature! To think it never succeeded in, never

even dreamed of, freeing itself from this slavery which weighed so heavily and unconsciously on

its destinies, on the course of its progress thus straitened and confined! Ah! Let us once more

bless our fortunate disaster!

Now that after many abortive trials and agonizing convulsions it has succeeded in taking

its final shape, we can clearly establish the essential characteristics of this modern civilisation of

which we are so justly proud. It consists in the complete elimination of living nature, whether

animal or vegetable, man only excepted. That has produced, so to say, a purification of society.

Secluded thus from every influence of the natural milieu into which it was hitherto plunged and

confined, the social milieu was for the first time able to reveal and display its true virtues, and

the real social bond appeared in all its vigour and purity.

If it has been possible for us to realise the most perfect and the most intense social life

that has ever been seen, it is thanks to the extreme simplicity of our strictly so-called wants. The

quota of absolute necessities being thus reduced to almost nothing, the quota of superfluities has

been able to be extended to almost everything. Since we live on so little, there remains abundant

time for thought. A minimum of utilitarian work and a maximum of æsthetic, is surely

civilisation itself in its most essential element. The room left vacant in the heart by the reduction

of our wants is taken up by the talents—those artistic, poetic, and scientific talents which, as they

day by day multiply and take deeper root, become really and truly acquired wants. They really

spring, however, from a necessity to produce, and not from a necessity to consume. I underline

this difference.

The error, at present recognised, of those ancient visionaries called socialists was their

failure to see that this life in common, this intense social life, they dreamt of so ardently, had for

its indispensable condition the æsthetic life and the universal propagation of the religion of truth

and beauty. The latter assumes the drastic lopping off of numerous personal wants. Consequently

in rushing, as they did, into an exaggerated development of commercial life, they were marching

in the opposite direction to their own goal. We can now comprehend the depth of the truly social

revolution which was accomplished from the days when the æsthetic activity, by dint of ever

growing, ended by vanquishing utilitarian activity. Henceforth in place of the relation of

producer to consumer has been substituted, as preponderating element in human dealings, the

relation of the artist to the art-lover. The ancient social ideal was to seek amusement or self-

satisfaction apart and to render mutual service. For this we substitute the following: to be one’s

own servant and mutually to delight one another. Henceforward, to insist once more, society

reposes, not on the exchange of services, but on the exchange of admiration or criticism, of

favourable or unfavourable judgments. The anarchical regime of greed in all its forms has been

succeeded by the autocratic government of enlightened opinion which has become supreme.

Now there is but a single passion for all its thousand names, as there is above but a single

sun. It is love, the soul of our soul and source of our art. That is the true sun which will never fail

us, which is never weary of touching and reanimating with the light of its countenance its lower

creations of yore, the first-born incarnations of the heart, in order to make them young once

more, in order to re-gild them with its dawns, and reincarnadine them with its setting splendours;

almost in the same fashion as it sufficed the other sun to compass with a single ray that august

summons to deck the earth, addressed to every ancient plant of the field, awakening it to bloom

anew, that grand yearly transformation scene, so deceptive and entrancing, which they named the

Spring, when there was still a Spring to name!

Markues

VON DER SCHENKENDEN TUGEND aus Also sprach Zarathustra von Friedrich Nietzsche

1

Als Zarathustra von der Stadt Abschied genommen hatte, welcher sein Herz zugethan war und deren Name lautet: „die bunte Kuh“ — folgten ihm Viele, die sich seine Jünger nannten und gaben ihm das Geleit. Also kamen sie an einen Kreuzweg: da sagte ihnen Zarathustra, dass er nunmehr allein gehen wolle; denn er war ein Freund des Alleingehens. Seine Jünger aber reichten ihm zum Abschiede einen Stab, an dessen goldnem Griffe sich eine Schlange um die Sonne ringelte. Zarathustra freute sich des Stabes und stützte sich darauf; dann sprach er also zu seinen Jüngern:

Sagt mir doch: wie kam Gold zum höchsten Werthe? Darum, dass es ungemein ist und unnützlich und leuchtend und mild im Glanze; es schenkt sich immer.

Nur als Abbild der höchsten Tugend kam Gold zum höchsten Werthe. Goldgleich leuchtet der Blick dem Schenkenden. Goldes-Glanz schliesst Friede zwischen Mond und Sonne.

Ungemein ist die höchste Tugend und unnützlich, leuchtend ist sie und mild im Glanze: eine schenkende Tugend ist die höchste Tugend.

Wahrlich, ich errathe euch wohl, meine Jünger: ihr trachtet, gleich mir, nach der schenkenden Tugend. Was hättet ihr mit Katzen und Wölfen gemeinsam?

Das ist euer Durst, selber zu Opfern und Geschenken zu werden: und darum habt ihr den Durst, alle Reichthümer in eure Seele zu häufen.

Unersättlich trachtet eure Seele nach Schätzen und Kleinodien, weil eure Tugend unersättlich ist im Verschenken-Wollen.

Ihr zwingt alle Dinge zu euch und in euch, dass sie aus eurem Borne zurückströmen sollen als die Gaben eurer Liebe.

Wahrlich, zum Räuber an allen Werthen muss solche schenkende Liebe werden; aber heil und heilig heisse ich diese Selbstsucht.

Eine andre Selbstsucht giebt es, eine allzuarme, eine hungernde, die immer stehlen will, jene Selbstsucht der Kranken, die kranke Selbstsucht.

Mit dem Auge des Diebes blickt sie auf alles Glänzende; mit der Gier des Hungers misst sie Den, der reich zu essen hat; und immer schleicht sie um den Tisch der Schenkenden.

Krankheit redet aus solcher Begierde und unsichtbare Entartung; von siechem Leibe redet die diebische Gier dieser Selbstsucht.

Sagt mir, meine Brüder: was gilt uns als Schlechtes und Schlechtestes? Ist es nicht Entartung? — Und auf Entartung rathen wir immer, wo die schenkende Seele fehlt.

Aufwärts geht unser Weg, von der Art hinüber zur Über-Art. Aber ein Grauen ist uns der entartende Sinn, welcher spricht: „Alles für mich.“

Aufwärts fliegt unser Sinn: so ist er ein Gleichniss unsres Leibes, einer Erhöhung Gleichniss. Solcher Erhöhungen Gleichnisse sind die Namen der Tugenden.

Also geht der Leib durch die Geschichte, ein Werdender und ein Kämpfender. Und der Geist — was ist er ihm? Seiner Kämpfe und Siege Herold, Genoss und Wiederhall.

Gleichnisse sind alle Namen von Gut und Böse: sie sprechen nicht aus, sie winken nur. Ein Thor, welcher von ihnen Wissen will!

Achtet mir, meine Brüder, auf jede Stunde, wo euer Geist in Gleichnissen reden will: da ist der Ursprung eurer Tugend.

Erhöht ist da euer Leib und auferstanden; mit seiner Wonne entzückt er den Geist, dass er Schöpfer wird und Schätzer und Liebender und aller Dinge Wohlthäter.

Wenn euer Herz breit und voll wallt, dem Strome gleich, ein Segen und eine Gefahr den Anwohnenden: da ist der Ursprung eurer Tugend.

Wenn ihr erhaben seid über Lob und Tadel, und euer Wille allen Dingen befehlen will, als eines Liebenden Wille: da ist der Ursprung eurer Tugend.

Wenn ihr das Angenehme verachtet und das weiche Bett, und von den Weichlichen euch nicht weit genug betten könnt: da ist der Ursprung eurer Tugend.

Wenn ihr Eines Willens Wollende seid, und diese Wende aller Noth euch Nothwendigkeit heisst: da ist der Ursprung eurer Tugend.

Wahrlich, ein neues Gutes und Böses ist sie! Wahrlich, ein neues tiefes Rauschen und eines neuen Quelles Stimme!

Macht ist sie, diese neue Tugend; ein herrschender Gedanke ist sie und um ihn eine kluge Seele: eine goldene Sonne und um sie die Schlange der Erkenntniss.

2

Hier schwieg Zarathustra eine Weile und sah mit Liebe auf seine Jünger. Dann fuhr er also fort zu reden: — und seine Stimme hatte sich verwandelt.

Bleibt mir der Erde treu, meine Brüder, mit der Macht eurer Tugend! Eure schenkende Liebe und eure Erkenntniss diene dem Sinn der Erde! Also bitte und beschwöre ich euch.

Lasst sie nicht davon fliegen vom Irdischen und mit den Flügeln gegen ewige Wände schlagen! Ach, es gab immer so viel verflogene Tugend!

Führt, gleich mir, die verflogene Tugend zur Erde zurück — ja, zurück zu Leib und Leben: dass sie der Erde ihren Sinn gebe, einen Menschen-Sinn!

Hundertfältig verflog und vergriff sich bisher so Geist wie Tugend. Ach, in unserm Leibe wohnt jetzt noch all dieser Wahn und Fehlgriff: Leib und Wille ist er da geworden.

Hundertfältig versuchte und verirrte sich bisher so Geist wie Tugend. Ja, ein Versuch war der Mensch. Ach, viel Unwissen und Irrthum ist an uns Leib geworden!

Nicht nur die Vernunft von Jahrtausenden — auch ihr Wahnsinn bricht an uns aus. Gefährlich ist es, Erbe zu sein.

Noch kämpfen wir Schritt um Schritt mit dem Riesen Zufall, und über der ganzen Menschheit waltete bisher noch der Unsinn, der Ohne-Sinn.

Euer Geist und eure Tugend diene dem Sinn der Erde, meine Brüder: und aller Dinge Werth werde neu von euch gesetzt! Darum sollt ihr Kämpfende sein! Darum sollt ihr Schaffende sein!

Wissend reinigt sich der Leib; mit Wissen versuchend erhöht er sich; dem Erkennenden heiligen sich alle Triebe; dem Erhöhten wird die Seele fröhlich.

Arzt, hilf dir selber: so hilfst du auch deinem Kranken noch. Das sei seine beste Hülfe, dass er Den mit Augen sehe, der sich selber heil macht.

Tausend Pfade giebt es, die nie noch gegangen sind; tausend Gesundheiten und verborgene Eilande des Lebens. Unerschöpft und unentdeckt ist immer noch Mensch und Menschen-Erde.

Wachet und horcht, ihr Einsamen! Von der Zukunft her kommen Winde mit heimlichem Flügelschlagen; und an feine Ohren ergeht gute Botschaft.

Ihr Einsamen von heute, ihr Ausscheidenden, ihr sollt einst ein Volk sein: aus euch, die ihr euch selber auswähltet, soll ein auserwähltes Volk erwachsen: — und aus ihm der Übermensch.

Wahrlich, eine Stätte der Genesung soll noch die Erde werden! Und schon liegt ein neuer Geruch um sie, ein Heil bringender, — und eine neue Hoffnung!

3

Als Zarathustra diese Worte gesagt hatte, schwieg er, wie Einer, der nicht sein letztes Wort gesagt hat; lange wog er den Stab zweifelnd in seiner Hand. Endlich sprach er also: — und seine Stimme hatte sich verwandelt.

Allein gehe ich nun, meine Jünger! Auch ihr geht nun davon und allein! So will ich es.

Wahrlich, ich rathe euch: geht fort von mir und wehrt euch gegen Zarathustra! Und besser noch: schämt euch seiner! Vielleicht betrog er euch.

Der Mensch der Erkenntniss muss nicht nur seine Feinde lieben, sondern auch seine Freunde hassen können.

Man vergilt einem Lehrer schlecht, wenn man immer nur der Schüler bleibt. Und warum wollt ihr nicht an meinem Kranze rupfen?

Ihr verehrt mich; aber wie, wenn eure Verehrung eines Tages umfällt? Hütet euch, dass euch nicht eine Bildsäule erschlage!

Ihr sagt, ihr glaubt an Zarathustra? Aber was liegt an Zarathustra! Ihr seid meine Gläubigen: aber was liegt an allen Gläubigen!

Ihr hattet euch noch nicht gesucht: da fandet ihr mich. So thun alle Gläubigen; darum ist es so wenig mit allem Glauben.

Nun heisse ich euch, mich verlieren und euch finden; und erst, wenn ihr mich Alle verleugnet habt, will ich euch wiederkehren.

Wahrlich, mit andern Augen, meine Brüder, werde ich mir dann meine Verlorenen suchen; mit einer anderen Liebe werde ich euch dann lieben.

Und einst noch sollt ihr mir Freunde geworden sein und Kinder Einer Hoffnung: dann will ich zum dritten Male bei euch sein, dass ich den grossen Mittag mit euch feiere.

Und das ist der grosse Mittag, da der Mensch auf der Mitte seiner Bahn steht zwischen Thier und Übermensch und seinen Weg zum Abende als seine höchste Hoffnung feiert: denn es ist der Weg zu einem neuen Morgen.

Alsda wird sich der Untergehende selber segnen, dass er ein Hinübergehender sei; und die Sonne seiner Erkenntniss wird ihm im Mittage stehn.

„Todt sind alle Götter: nun wollen wir, dass der Übermensch lebe.“ — diess sei einst am grossen Mittage unser letzter Wille! —

Also sprach Zarathustra.

ON THE BESTOWING VIRTUE from Thus Spoke Zarathustra by Friedrich Nietzsche, translated by Adrian Del Caro

1

When Zarathustra had taken leave of the city, which was dear to his heart and whose name was The Motley Cow, many who called themselves his disciples followed him, and they provided him escort. Thus they came to a crossroads; then Zarathustra told them he wanted to walk alone now, for he was a friend of walking alone. In parting, however, his disciples presented him with a staff upon whose golden knob a snake encircled the sun. Zarathustra was delighted with the staff and leaned on it; then he spoke thus to his disciples.

Tell me now: how did gold come to have the highest value? Because it is uncommon and useless and gleaming and mild in its luster; it bestows itself always.

Only as the image of the highest virtue did gold come to have the highest value. Goldlike gleams the gaze of the bestower. Golden luster makes peace between moon and sun.

Uncommon is the highest virtue and useless, it is gleaming and mild in its luster: a bestowing virtue is the highest virtue.

Truly, I guess youwell,my disciples: likemeyou strive for the bestowing virtue. What would you have in common with cats or wolves?

This is your thirst: to become sacrifices and gifts yourselves, and therefore you thirst to amass all riches in your soul.

Insatiably your soul strives for treasures and gems, because your virtue is insatiable in wanting to bestow.

You compel all things to and into yourselves, so that they may gush back from your well as the gifts of your love.

Indeed, such a bestowing love must become a robber of all values, but hale and holy I call this selfishness.

There is another selfishness, one all too poor, a hungering one that always wants to steal; that selfishness of the sick, the sick selfishness. With the eye of the thief it looks at all that gleams; with the greed of hunger it eyes those with ample food; and always it creeps around the table of the bestowers.

Sickness speaks out of such craving and invisible degeneration; the thieving greed of this selfishness speaks of a diseased body.

Tell me, my brothers: what do we regard as bad and worst? Is it not degeneration?–Andwe always diagnose degeneration where the bestowing soul is absent.

Upward goes our way, over from genus to super-genus. But a horror to us is the degenerating sense which speaks: “Everything for me.”

Upward flies our sense; thus it is a parable of our body, a parable of elevation. Such elevation parables are the names of the virtues.

Thus the body goes through history, becoming and fighting. And the spirit – what is it to the body? The herald of its fights and victories, companion and echo.

Parables are all names of good and evil: they do not express, they only hint. A fool who wants to know of them!

Pay attention, my brothers, to every hour where your spirit wants to speak in parables: there is the origin of your virtue.

There your body is elevated and resurrected; with its bliss it delights the spirit, which becomes creator and esteemer and lover and benefactor of all things.

When your heart flows broad and full like a river, a blessing and a danger to adjacent dwellers: there is the origin of your virtue.

When you are sublimely above praise and blame, and your will wants to command all things, as the will of a lover: there is the origin of your virtue.

When you despise pleasantness and the soft bed, and cannot bed down far enough away from the softies: there is the origin of your virtue.

When you are the ones who will with a single will, and this turning point of all need points to your necessity: there is the origin of your virtue. Indeed, it is a new good and evil! Indeed, a new, deep rushing and the voice of a new spring!

It is power, this new virtue; it is a ruling thought and around it a wise soul: a golden sun and around it the snake of knowledge.

2

Here Zarathustra was silent for a while and looked with love at his disciples. Then he continued to speak thus – and his voice had transformed.

Remain faithful to the earth,my brothers, with the power of your virtue! Let your bestowing love and your knowledge serve the meaning of the earth! Thus I beg and beseech you.

Do not let it fly away from earthly things and beat against eternal walls with its wings! Oh, there has always been so much virtue that flew away!

Like me, guide the virtue that has flown away back to the earth – yes, back to the body and life: so that it may give the earth its meaning, a human meaning!

In a hundred ways thus far the spirit as well as virtue has flown away and failed. Oh, in our body now all this delusion and failure dwells: there they have become body and will.

In a hundred ways thus far spirit as well as virtue has essayed and erred. Indeed, human beings were an experiment. Alas, much ignorance and error have become embodied in us!

Not only the reason of millennia – their madness too breaks out in us. It is dangerous to be an heir.

Still we struggle step by step with the giant called accident, and over all humanity thus far nonsense has ruled, the sense-less.

Let your spirit and your virtue serve the meaning of the earth, my brothers: and the value of all things will be posited newlyby you! Therefore you shall be fighters! Therefore you shall be creators!

Knowingly the body purifies itself; experimenting with knowledge it elevates itself; all instincts become sacred in the seeker of knowledge; the soul of the elevated one becomes gay.

Physician, help yourself: thus also you help your sick. Let that be his best help, that he sees with his own eyes the one who heals himself.

There are a thousand paths that have never yet been walked; a thousand healths and hidden islands of life. Human being and human earth are still unexhausted and undiscovered.

Wake and listen, you lonely ones! From the future come winds with secretive wingbeats; good tidings are issued to delicate ears.

You lonely of today, you withdrawing ones, one day you shall be a people: from you who have chosen yourselves a chosen people shall grow–and from them the overman.

Indeed, the earth shall yet become a site of recovery! And already a new fragrance lies about it, salubrious – and a new hope!

3

When Zarathustra had said these words, he grew silent like one who has not spoken his lastword.Long heweighed the staff in his hand, doubtfully. Finally he spoke thus, and his voice had transformed.

“Alone I go now,my disciples! You also should go now, and alone! Thus I want it.

Indeed, I counsel you to go away from me and guard yourselves against Zarathustra! And even better: be ashamed of him! Perhaps he deceived you.

The person of knowledge must not only be able to love his enemies, but to hate his friends too.

One repays a teacher badly if one always remains a pupil only. And why would you not want to pluck at my wreath?

You revere me, but what if your reverence falls down some day? Beware that you are not killed by a statue!

You say you believe in Zarathustra? But whatmatters Zarathustra! You are my believers, but what matter all believers!

You had not yet sought yourselves, then you found me. All believers do this; that’s why all faith amounts to so little.

Now I bid you lose me and find yourselves; and only when you have all denied me will I return to you.

Indeed, with different eyes, my brothers, will I then seek my lost ones; with a different love will I love you then.

And one day again you shall becomemy friends and children of a single hope; then I shall be with you a third time, to celebrate the great noon with you.

And that is the great noon, where human beings stand at the midpoint of their course between animal and overman and celebrate their way to evening as their highest hope: for it is the way to a new morning.

Then the one who goes under will bless himself, that he is one who crosses over; and the sun of his knowledge will stand at noon for him.

‘Dead are all gods: now we want the overman to live.’ – Let this be our last will at the great noon!” –

Thus spoke Zarathustra.

Jess Zamora-Turner

Linden flower, elderflower, lemon balm, flowering thyme and cornflower.